Breadcrumb

Professors combating mosquito-borne diseases while training future researchers

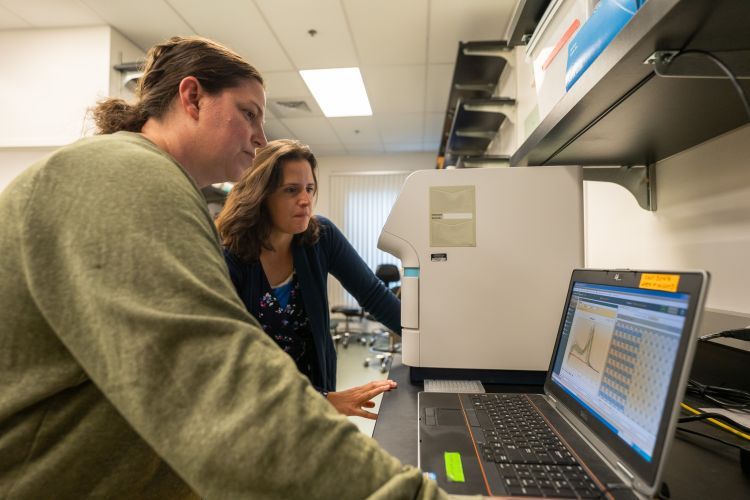

(L-R) Associate Professor of Biology Tara Thiemann and Assistant Professor of Psychology Carla Strickland-Hughes

Mosquitoes in Northern California that can transmit West Nile virus are becoming resistant to insecticide. Associate Professor of Biology Tara Thiemann is trying to figure out why, while training new scientists at the same time.

“We’re comparing samples from 10 to 15 years ago to present day to see if we can figure out the triggers,” Thiemann said. “The goal is to give vector control districts information about resistance that they can use to inform their choices about what works best to control the mosquitoes in their area.”

Thiemann was awarded $500,000 in new research funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to study the issue over the next five years. She will work with Assistant Professor of Psychology Carla Strickland-Hughes, who is evaluating the effectiveness of public outreach campaigns for reducing vector-borne diseases (illnesses spread by organisms such as ticks or mosquitoes).

Human behaviors, such as eliminating standing water and wearing insect repellent, can reduce breeding grounds and vector biting.

“These efforts are only effective if people have access to them, understand them, and actually make a meaningful change in their behaviors,” Strickland-Hughes said.

Their research is part of a $10 million grant awarded to the Pacific Southwest Center of Excellence in Vector-Borne Diseases, which is led by the University of California, Davis. The center’s goal is to manage and prevent mosquito and tick-borne diseases.

Pacific is one of seven institutions collaborating on the research. Each investigator has their own area of specialty focused on vector-borne diseases.

“The idea is that we are all answering questions that give information about the best ways to prevent vector-borne diseases, but also there is this training component,” Thiemann said. “We're all training new scientists who will then become the next generation of the public-health workforce.”

The Zika outbreak in 2016 highlighted the need for more scientists. The virus was transmitted by mosquitoes and declared a public health emergency of international concern by the World Health Organization.

“The outbreak triggered people to ask, ‘would the United States be ready if we had an introduction of a vector-borne disease?’ and the assessment was that we don't have enough vector biologists and people who work in public health that would help us be prepared,” Thiemann said.

Thiemann and Strickland-Hughes’ research will provide hands-on experiences for students, such as extracting DNA from mosquitoes, DNA sequencing, conducting surveys and field observations.

“It’s exciting to help them see how these research skills that they're learning in our coursework can be applied to real-world questions,” Strickland-Hughes said.